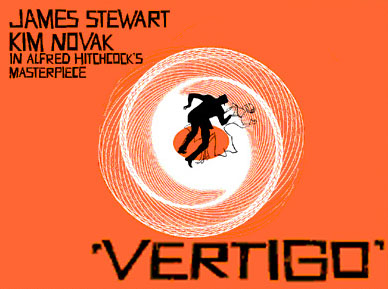

Vertigo is the greatest

film ever made, according to the prestigious Sight and Sound poll conducted

amongst a wide selection of film critics and academics once a decade, finally

trumping Citizen Kane, which held the top spot for the past five

decades. Although it is of course pointless to name any film as the best ever –

such a reputation will only damage the film in the eyes of those yet to see it,

creating a level of expectation that no film could ever life up to – it does

represent the odd staying power of Vertigo.

Vertigo is nominally the

story of a detective called Scotty (James Stewart) following Madeleine (Kim

Novak) through the streets of San Francisco at the behest of her husband Elster

(Tom Helmore), who seems to believe that she has been possessed by the spirit

of the tragic Carlotta Valdes, who may be related to Madeleine and who

committed suicide years before. The film was reviled when it was first released

and it was slow to gain a following amongst critics and audiences. It wasn’t

until the 1970s that the film was becoming less and less easy to dismiss as a

languorous exercise in dull melodramatic excess with a ridiculous twist, and it

has crept up the Sight and Sound poll ever since (appearing 8th in

1982, 4th in 1992 and 2nd in 2002).

Vertigo isn’t the greatest

film ever made – and, for my money, Sight and Sound where nearer the mark with Citizen

Kane – but it does have its own distinct and eerie fascination, which will

force the viewer to go back and watch it endlessly, a mysteriousness that looks

forward to films like Persona and Mulholland Dr. As such, it is

difficult to write about without spoilers.

Vertigo is a film about

passion and love and trying to overcome the past, though all of these themes

are problematized (the film is rarely as simple as it looks). Scotty falls in

love with Madeleine as he follows her through the streets of San Francisco and

beyond, though it is never clear when his obsessive tailing becomes obsessive

love. The scenes of Scotty following Madeleine in his car are long and shots

are held for much longer than they seem to need to be, but they convey an

almost hypnotic quality, capturing the obsession and the strange intimacy that

must come with following a stranger without their knowledge. But has Scotty

fallen in love with Madeleine herself, or with Madeleine as Carlotta, since he

is supposedly following Madeleine only when she has been ‘possessed’ by

Carlotta. These scenes are complicated further on a rewatch when we know that

Scotty is not following Madeleine at all, but an actress called Judy Barton who

is pretending to be Madeleine. Scotty’s love, already perverse, is made

stranger by the fact that he may be in love with three women or fragments of

all three.

Either that or Scotty himself is

simply a nut – Hitchcock leaves us little hints that Scotty himself is not

entirely sane, though they remain subtle until the film’s final act. An example

of one such hint follows Madeleine’s/ Carlotta’s/ Judy’s jump into San

Francisco Bay. Scotty saves her, brings her back to his house and undresses her

and puts her in bed. After this scene, Scotty seems to be much more enthralled

with her, begging the question of what changed during the film’s fade out. The

film becomes a subversive love story, the kind that Nicholas Ray might have

made with swelling operatic music, ghostly locations and crashing waves.

Scotty promises to save Madeleine

from Carlotta, but he fails. Thanks to his vertigo, he cannot climb up to the

top of the clock tower to save Madeleine from throwing herself to her death.

Numb with guilt, Scotty wanders through San Francisco, revisiting the locations

where he followed Madeleine. He has a nightmare with ghosts and open graves and

appears to go into a comatose state. There is a theory that the film ends here,

or at least that the action does. The rest of the film takes place in Scotty’s

head as he tries to find a way to resolve his guilt, inventing a mad story

about Elster hiring an actress to play Madeleine in order to get away with the

murder of the real Madeleine. Judy as Madeleine lured Scotty to the clock

tower, knowing he couldn’t get to the top and yet would nevertheless be able to

act as an eyewitness to Madeleine’s supposed suicide. Scotty, by inventing a

story to relieve himself of the guilt of his failure to protect the real

Madeleine, is trying to overcome the past by changing his perception of what

that past was.

The above is just one

interpretation and not a particularly interesting one since it imposes a little

too much sense on this so fascinatingly odd film, but it does reveal in its own

way the appeal of Vertigo, a film that is simple and yet incredibly

ambiguous, supporting so many different possibilities.

Taking the final act at face

value, we are left with a bizarre love story. By suddenly seeing Judy on the

street, Scotty starts to try to bring Madeleine back to life (not realising

that Judy was the version of Madeleine that he fell in love with), buying Judy

new clothes and altering her appearance. Judy plays along, because she did

genuinely fall in love with Scotty while she was playing Madeleine (which begs

the question of how much Judy there was in the version of Madeleine that Scotty

fell in love with), but now she is left with the odd situation of being in love

with a man who is really in love with a different woman and the same woman.

Judy becomes jealous of Madeleine, even though Madeleine is really her.

Meanwhile, Scotty tries to recreate Madeleine, getting increasingly obsessive.

As an example of Hitchcock’s

strategy with Vertigo and the film multiplicity of meaning, when Scotty

is begging Judy to dye her hair to match Madeleine’s hair colour, she refuses

and he says, “It can’t matter to you.” This line has two possible meanings. The

first is that Scotty has indeed gone mad – of course it would matter to Judy

that she dye her hair. The second is that Scotty knows that Judy has already

played Madeleine and has, hence, dyed her hair before so it shouldn’t matter to

her now. This suggests, however, that Scotty is complicit in the knowledge of

what happened to the real Madeleine, but would prefer to ignore it until he can

get his version of Madeleine back from the dead one more time. Only after he

has finally got his Madeleine back – in a scene in which the green neon of the

sign of Judy’s grotty hotel and Scotty’s undying, obsessive love for Madeleine

seems to have a transformative power, bringing Scotty and Madeleine back

through space and time to the moment when they were last together – he is able

to allow himself to notice the giveaway necklace.

Vertigo is

not a film that can support any particular interpretation. Even taking the plot

at face value, there are some inconsistencies that don’t fit, such as

Madeleine’s/ Judy’s disappearance from the McKittrick Hotel early in the film. Vertigo

is a strange, eerie and perverse love story and it is the story of Scotty’s

love for Madeleine (whoever she is and wherever in time she is) that is the

subject of the film. It is a film of love and loss, shot through with obsession

and darkness but also tenderness and real feeling, perfectly paced and wholly

engrossing. The music swells operatically, waves crash on the shore just as the

couple share their first kiss and everything is shot through with surreal

colour and hazy filters. All one needs to see is that revolving shot when

Scotty kisses Judy dressed up as Madeleine and is transported to know that, for

all of Hitchcock’s tricks, Vertigo is utterly genuine.

Vertigo is being screened at the Dungannon Film Club at 7:30pm on Wednesday 10 September.

No comments:

Post a Comment